The Story of the Market Fee

Kirivoan is a commune located in the Kampong Speu province, about 70 km West of Phnom Penh, on the way to the well-known Kirirom National Park. Most people living here are farmers: Beside rice, they plant watermelons, sugar cane, yam roots and other plants, both for their own consumption and for income generation. They normally take their produce to the nearby Tropeang Kroleung market, where fruit, vegetables and other agricultural goods from the whole district are sold. However, back in 2011, while we were working on a project in their commune, many villagers from Kirivoan complained about the high fee the company running the market was collecting. People from the community wanted to know whether this fee, which could amount to 1000 riel a day, was actually endorsed by the local authorities – or rather the result of an abuse.

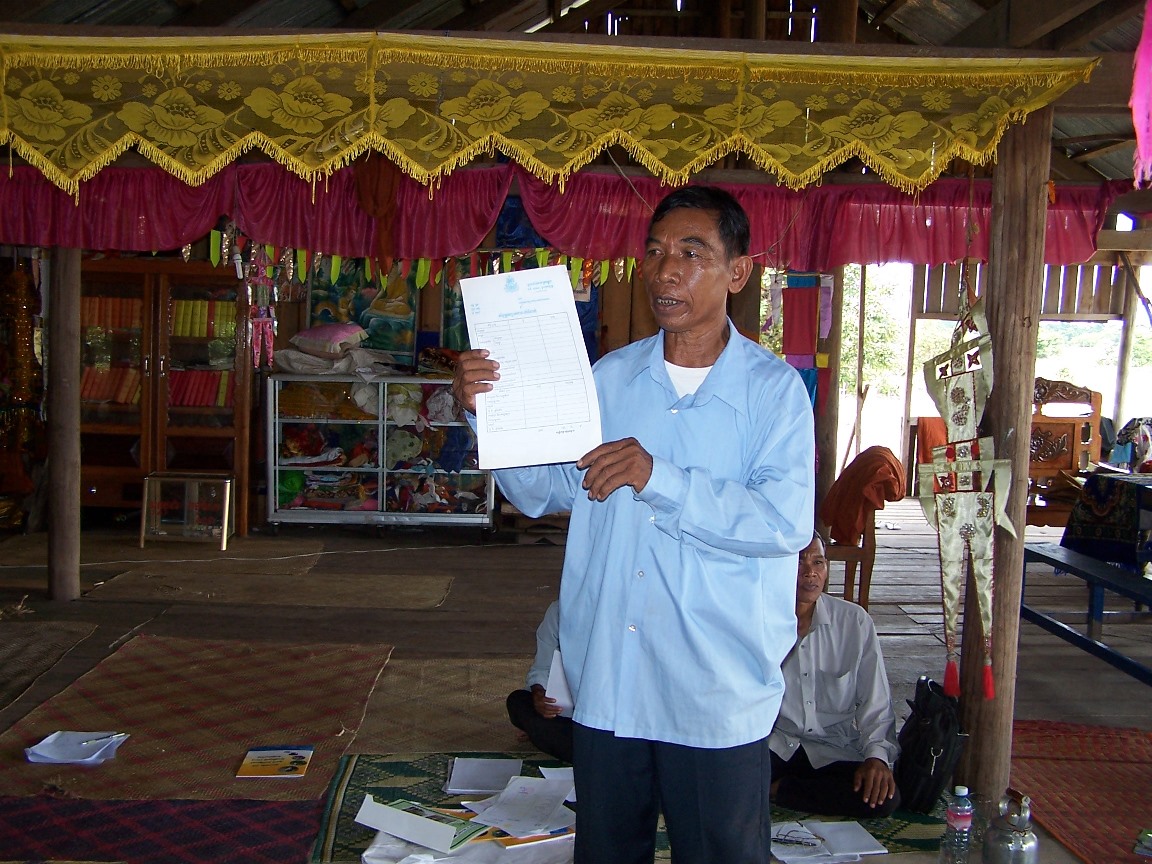

So, together with our project partners from Mlup Baitong, we invited the commune councillors and other relevant decision makers to join a forum with the ordinary citizens and discuss this topic. It soon turned out that neither the commune, nor the district administration had a copy of the contract with the private company managing the market, and the latter did not reply to our invitation. It took almost four months of regular meetings, where community leaders again and again raised the issue, until we all finally found out that, according to the contract signed at the provincial level, that daily fee was not supposed to exceed 300 riel. Only then did the company acknowledge it had constantly overcharged sellers, promising to stay within the negotiated framework from that moment on.

Our Focus on the Grassroots

This is a story about what local mobilization and participation can achieve, but it equally shows how difficult it is to repair the damage done by remote, unilateral and opaque decision making. At the same time, this is not an isolated case: In our more than 15 years of activity at the grassroots level, we’ve heard so many other similar stories, all pointing in the same direction. From the very beginning, API has been committed to advocating for and enabling citizens to get involved in the business of making their voices heard, exercising democratic control and holding the Government accountable. As we soon found out, this is much easier to achieve in villages, districts and even provinces, than on the national stage, where politics plays a much bigger role and strong demands might be misinterpreted, especially in the current context.

On the other hand, however, democratic participation at the local level is most probably both a prerequisite and some sort of guarantee for the sustainability of any future steps towards meaningful citizens’ engagement in bigger arenas. In a country like Cambodia, where a solid majority is still rooted in relatively small communities, it is hard to believe that active involvement in the kind of abstract topics which are discussed in Parliament can happen on a large scale and with lasting results, if this does not occur locally, with more concrete issues first. Against this background, we consider our ongoing push for local democratic participation as an important effort in the right direction.

It Takes Two to Tango

For citizens to be able to have a say in the decisions shaping the future of their communes, districts or provinces, they first of all have to be given real opportunities to do so. This means, for example, that regular fora or consultations must be held not merely as monologues by the authorities or as polite formalities, but as actual debate arenas where topics can be brought up by anyone and the results of the discussions are open, rather than predetermined. Furthermore, citizens must be given a chance to systematically monitor the actions taken by local officials, to rate and comment on their performance, and ask (sometimes unpleasant) questions. For Cambodia, which is a country where the traditional idea of authority is still very present, this is a big step forward, yet we insist that local councillors and other decision makers should really stop thinking of themselves as untouchable figures, and start understanding that they are accountable to their constituencies.

At the same time, it is naive to believe that, once members of the local communities are given the slightest opportunity to express themselves, they will spontaneously do it in an articulate and most productive way. Not only various forms of (real or perceived) social disadvantage – such as being poor, lacking a formal education, belonging to an ethnic minority or simply being a woman – might and often do in fact prevent them from making their voices heard. Even if they overcome these obstacles or do not belong to any of these groups in the first place, social participation does not come naturally, but requires a specific mind-set (that of an actively involved right-holder, as opposed to a passive subject), and also certain skills such as the basics of public speaking or advocacy.

The First Push for Decentralisation

This is why, at API, we have been focusing on both sides of this equation – citizens and their legitimate demands, often represented by community based organisations, on the one hand, and local officials as duty bearers, on the other. Both groups are in need of various forms of capacity building, if their interaction is to become a fruitful cooperation based on the acknowledgement of basic political freedoms, rational dialogue and constructive approaches. Two of our earliest projects – “Grassroots Democracy” and “National Forum for Discussion, Sharing and Learning” (2008-2010) – thus focused on bringing the demand and the supply side to the same table, but only after giving them some of the tools needed to address community issues, including tricky ones such as the governance of land and natural resources. You can find more information about these early efforts in our annual reports .

However, we quickly saw ourselves confronted with difficulties, as the good will of the local authorities proved to be insufficient in the absence of real decentralisation. Decisions mainly affecting a village or a small neighbourhood were often taken at much higher government levels, with little, if any consultation, just like in the story of the market fee. The Law on the Administrative Management of the Capital, the Provinces, Districts (in Khmer, “khan”, if they are in Phnom Penh, or “srok”, outside of it), and Municipalities was adopted in 2008, and it provides sub-national councils with general mandates in promoting the well-being of people in its jurisdictions. Under these mandates, councils at all levels have the right to carry out functions with full authority. All these functions are considered as “permissive”, that is to say that local representatives can choose what issues they address based on the priorities they set and the resource available. It is, nevertheless, unclear whether this really means full blown local autonomy. Starting from 2010, the Government has engaged on a long path to clarifying the matter, and has drafted various decentralisation programmes to be implemented by the newly created National (inter-ministerial) Committee for Sub-National Democratic Development (NCDD).

Using this framework, API was able to better pursue its goals by implementing more ambitious projects aimed at more systematic capacity building for both local officials and the civil society. Between 2011 and 2013, one important initiative targeted, for instance, district councils and community based organisations in the same districts, with the support of DanChurchAid and Bread for the World/EED. Another one, funded by the World Bank and the Asia Foundation, concentrated on making the newly established One Window Service Offices more responsive to feedback given by the general public and the small businesses who use these public services. Our reports on these projects can be downloaded here and here. Meanwhile, we kept up our lobbying efforts, pushing for a more substantial decentralisation.

Towards Real Local Autonomy

As a result, by 2015, several ministries started taking more courageous steps to transfer and delegate essential service delivery functions to districts and municipalities. But this transfer process has been difficult and slow. At the beginning, the functions transferred were not implemented in an effective way, because local authorities often lacked the financial and human resources needed in order to fulfil their new roles. The Ministry of the Economy and Finances had to create conditional grant mechanisms at the disposal of sub-national administrations (e.g., a fund for solid waste management), while the Ministry of Civil Service had to develop a separate statute for the decentralized personnel, which was approved by the NCDD in 2016.

The government also tried to operationalize a “Sub-National Investment Fund”, and to provide local authorities with the power to increase discretionary funding by identifying local revenue sources. Moreover, a “sub-national planning policy” was sketched, supported by “revised planning guidelines” and indicating the needs and mechanisms for ensuring inclusive planning and budgeting at the capital, provincial, municipal, district and commune levels. Local councils are now required to come up with a 5-year development plan, on the basis of which they are expected to formulate a 3-year rolling investment programme, which in turn should serve as a framework for the preparation of annual budget plans.

While API supported and encouraged all these reforms, we also noticed that challenges remained. Hierarchical relations persisted between various levels of the public administration, budgets and personnel were still insufficient to address the needs, and, above all, the lack of capacity continued to pose serious difficulties in drafting and implementing ambitious development plans. Our project called “Strengthening Democratic Governance” (2014-2016) tried to address some of these issues, while at the same time emphasizing the need for true participation by diverse categories of citizens, including women and vulnerable groups. Our report is available here.

Demanding Social Accountability

The decentralisation reforms initiated by the Government, although still incomplete, have laid the groundwork for a more comprehensive approach to the topic of local democratic participation. On the one hand, the de-concentration of public services has been playing an increasing role. Furthermore, local authorities have been delegated certain attributions in social and economic development, while partnerships between administrations, the private sector and the NGOs have been promoted in order to achieve these goals. Finally, in recent years, Cambodia has also officially become part of a broad, internationally backed reform agenda known as “Implementing the Social Accountability Framework” (I-SAF). This effort is now assumed by the Government, and it requires a close cooperation with the civil society, in order to have the performance of public service providers and local authorities constantly monitored and assessed by citizens. In general, it can be said that this new approach stresses a broader institutional participation, with multiple stakeholders on both sides of the table, and more complex relations between them.

API joined the I-SAF effort with a first project in the Kampot province (2016-2018). This initial engagement was very much a hands-on attempt to provide citizens and community based organisations with real opportunities to express their opinions about the public services offered by health centres, primary school and commune administrations, and subsequently follow up on this feedback. In Banteay Meas Khang Lech, for instance, villagers used to have mixed feelings about their health centre, because, as Chan Yong, a local in her 50s said, “waiting to be seen by someone there could take long hours”. Nonetheless, the debate created by the poor rating these services received seems to have led to real change. By the time our project had been completed, the woman saw “a lot of improvements, especially more attention from the staff, more promptitude, and also much cleaner toilets”. Indeed, the director of the health centre also confirmed that local residents visited it more often once they had been convinced that their voices were actually being taken into account. A detailed report on this first I-SAF initiative can be found here.

Participation Today

Against the background of the political changes which have occurred in Cambodia after the main opposition party was dissolved in 2017, API has had to reconfigure its programmes. As many local officials were replaced and there are fundamental questions about their democratic legitimacy in this new context, we have decided to concentrate mostly on the demand side of the social contract, offering ordinary citizens and civil society organisations the tools and abilities they need in order to keep exercising control over the performance of the authorities. We strongly believe that active participation in local decision-making processes has become even more essential, since in the absence of real political opponents this is the only way to hold officials accountable.

Therefore, API has embarked on a sustained effort to make broad civil participation the norm everywhere, harness innovative technology in order to improve social accountability, and particularly focus on the rights and demands of women, youth and vulnerable groups. Most of our projects are currently dedicated to this thematic area – within or beside the I-SAF reform agenda – and they are covering almost all provinces in the country. You can find more details about our current work here . At the end of the day, what we are aiming for is nothing less than creating a grassroots democratic habit everywhere in Cambodia.