Whether in a society there is general access to public information obviously has broad implications for the way things work in the economy, in politics, in administration, in health and education, as well as in many other sectors directly affecting everyday life. A culture of transparency encourages citizens to actively participate in decision making, at the same time allowing them to make informed individual choices. Secrecy, on the other hand, is often hiding abuse and it thwarts people’s legitimate attempts to plan for their own future and hold authorities accountable.

Legal Background

The Cambodian Constitution provides only a limited specific reference to the right of access to information held against public bodies. Article 41 recognizes that citizens have the freedom to express their ideas, the freedom of the press, the freedom of publication and the freedom of assembly. Thus, the question of whether this article provides a clear and inclusive guarantee of a right to access information remains open. Most importantly, it is not clear what the term “freedom of the press” actually involves, so there has been an ongoing debate as to whether a specific right of access to information should be introduced in legislation in order to make sure that people can fully exercise it in their relations with any public institution, or even with private entities, to the extent those accomplish public functions or their activities affect the citizens in significant ways.

Beside the Constitution, there are a number of laws containing limited provisions on the access to information in certain sectors or vis-à-vis certain institutions. However, here again, things are not as clear as they should be, so, in practice, both the interpretation and the implementation of these provisions vary widely across the country. Thus, for example, although these legal texts specify that some authorities need to disclose non-confidential information to the public, there is neither a clear definition of “confidential”, nor is there any mention of sanctions against officials who do not release the requested information.

Our Stance

In this debate, there is a broad consensus among civil society, based on the recommendations of UN bodies and on the relevant sustainable development goals (SDGs) Cambodia has acknowledged. Along with many other local and international NGOs, as well as most legal experts, API has always strongly believed in the necessity of making the right of access to information explicit and specifying its implications in the framework of a separate law which should also spell out concrete procedures for requesting public information, clear deadlines for the authorities to respond to these requests, concrete and parsimonious limitations to this right, and so on. All this is in line with the best practices numerous other countries have developed and followed, so Cambodia does not need highly innovative approaches in this respect. What it needs is rather a stronger political will to pass and subsequently implement legislation. And a broadly shared culture of transparency to support these institutional steps.

The Early Days

In 2004, the Government formally acknowledged the need for a legal text, “in order to create transparency, reduce corruption and promote confidence in the Government by the citizens of Cambodia”. During the following three years, API organised public workshops and conferences involving government officials, members of civil society, local and international NGOs, as well as members of the general public. Against this background, the Council of Ministers mandated the Ministry of National Assembly Senate Relations and Inspections (MoNASRI) to draft a policy paper on access to information that would lay the groundwork for the development and adoption of a law. This paper was finally produced and published in 2007.

From the Policy Paper to the First Draft

After seeing this first, albeit timid step taken, API embarked on a path of sustained initiatives in order to build up pressure for more substantial progress on the law-making front. Thus, by implementing the project “Support to Improved Access to Information in Cambodia” (2008-2012, funded by the Danish International Development Agency), we focused on enhancing the general public’s access to state institutions and parliamentary debates through a coordinated campaign that encouraged the Government and the National Assembly to speed up the legislative process and develop a culture of maximum information disclosure. A parallel effort supported by the British Embassy in Phnom Penh aimed at creating a professional civil society lobby group that would actively engage with the National Assembly, pushing for the adoption of anti-corruption and access to information laws. More details are available here and here.

As a result, a civil society working group (FoIWG) was established in order to analyse both the policy paper itself, and subsequent documents, as well as to make recommendations to ministerial officials and members of the Parliament. Meanwhile, one of the opposition parties active back then submitted its own legislative proposal on access to information, but this attempt was not successful. By 2013, however, the task of drafting the legal text was delegated to the Ministry of Information, which proved to have a better understanding of the issues involved. A new API initiative funded by DanChurchAid (DCA) focused mainly on raising awareness about the importance of access to information at the local level, by producing training curricula directed to commune councils and community based organisations. Some of these materials can be consulted here , and our report can be downloaded here.

Our project called “Improving Access to Public Information” (IAPI, 2013-2015) was a further milestone on the way to increasing transparency for both the public and sub-national authorities. We regard this issue not only as fundamental to effective participation and accountability in local governance, but also as one of the factors which indirectly contribute to poverty reduction and equity among social groups. The final report of this important initiative supported by the EU, DCA, Bread for the World, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Open Society Institute (OSI) can be read here. In 2016, a committee of the Ministry of Information finally released a first draft of the law for civil society organisation to make comments. The text contained 9 chapters and 36 articles that aimed at ensuring the public’s right to and freedom of access to information, yet most independent analyses showed that international standards were only partially met by the provisions.

Towards an Improved Version

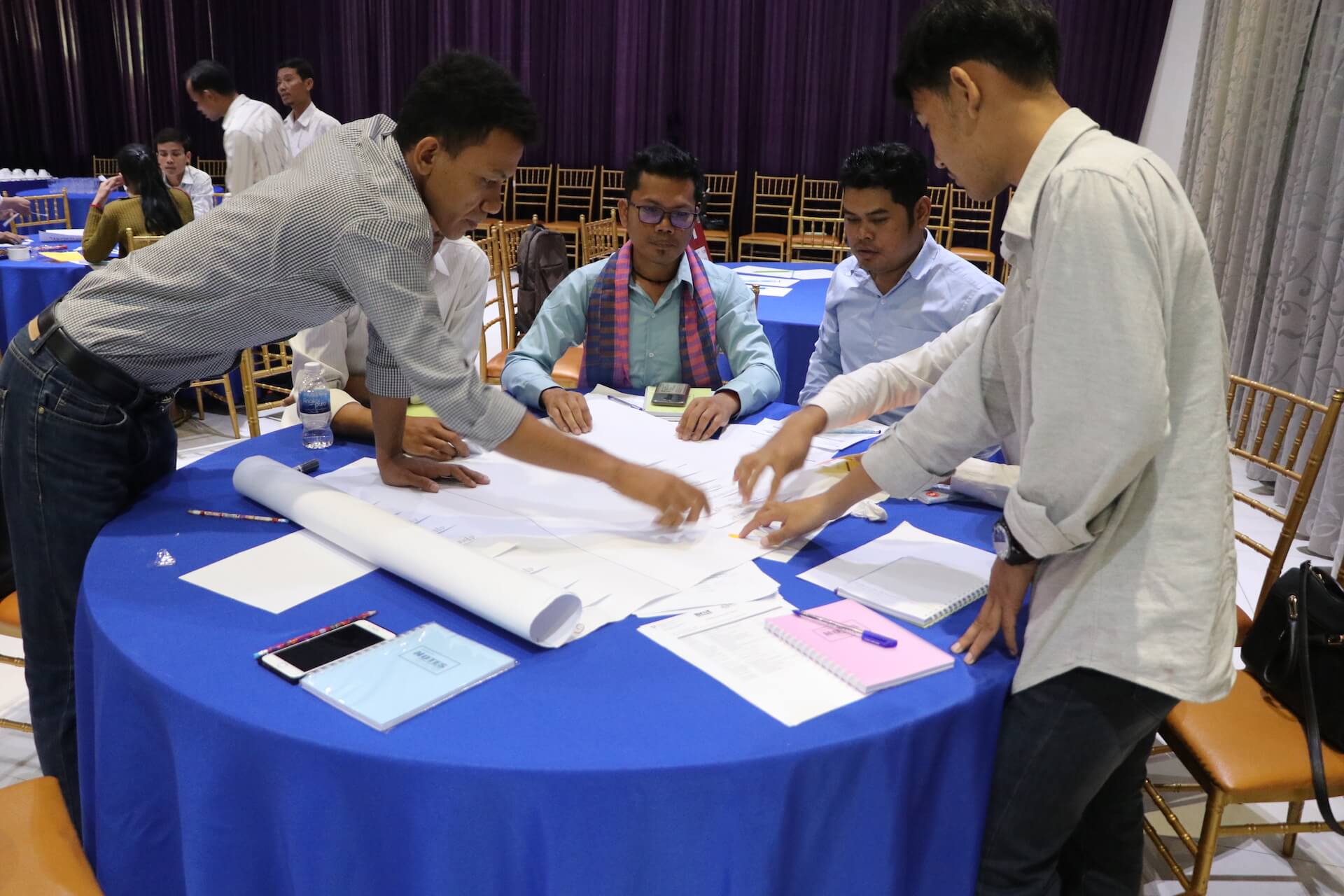

In the run-up to the official adoption of a final draft for this law, a number of API projects played a key role in mobilizing support, ensuring a significant amount of participation by various groups and organisations, creating synergies, organising numerous public debates and advocating for improvements in the legal text. Among these projects, first of all we would like to mention an initiative funded by UNESCO and the Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (SIDA), which concentrated on bridging the gap between Government and citizens and enabling a participatory law-making process. During this period (2014-2018), API helped consolidate the technical working group (now called A2IWG) where civil society gives feedback on the text and provides regular updates via the media. We also initiated a considerable number of consultative fora, where representatives of different media, human rights, health, education, youth or women’s organisations discussed the topic and made concrete proposals. An independent evaluation report emphasizing the achievements of this effort can be downloaded here.

Another important step we took in the same direction was financed by the EU, under the name “Promoting Good Governance by Increasing Access to Information and Strengthening the Independent Media” (2015-2018). Together with DCA and with our colleagues from CCIM, we offered intensive trainings to journalists and community based organisations in an effort to improve their professionalism and the quality of the media content. At the same time, we also trained representatives of the local authorities in order to build their capacity to respond to the legitimate information requests by journalists and citizens. More details about this project can be read here.

A number of other initiatives such as “I-SAF” or “One Window Service Offices”, to name but a few, primarily focused on subnational democratic participation, but also had a strong access to information component. We managed, for instance, to convince authorities to disclose the fees to be applied by operators of public transportation in communes and districts – a big achievement, given that, in Cambodia, the official price of these services used to be a mystery. You can find out more about these and similar initiatives here. In 2018, the final draft for the A2I law was released. It still falls short of fully meeting international standards and expectations by the local civil society, hence the need for further improvements. However, it is at least assumed by the Government, and therefore a solid base for future work.

The Current Situation

Since 2018, the legal text has been awaiting its discussion in the Council of Ministers, the final step before being sent over to the National Assembly and Senate for parliamentary debate and, eventually, being adopted. Numerous changes are still needed, if what we want is a good law, so API is keeping up its advocacy efforts. Yet, even when this long process finally comes to completion, this is not the end of the story. Our experience in the past few decades has shown that in Cambodia, like in many other developing countries, passing a law is one thing, but making its provisions part of reality is quite another. Broad participation by various segments of society is essential here, because it is only under this premise that the future law can find acceptance, and therefore be sustainably and successfully implemented. Against this background, it is quite clear that engaging all potentially concerned actors in this push is not merely an exercise in getting a critical mass of support, but it also lays the foundations of a meaningful application of the legal provisions in all fields of social life.

Therefore, on the one hand, API is keeping up its lobbying activities and is closely monitoring the legislative process. Here, it is worth noting that other legal texts, such as an Interior Ministry sub-decree on state secrecy or a law on whistle-blower and witness protection are currently being drafted and could have an impact on the provisions of the future A2I law as well. But, on the other hand, we are mostly concentrating on promoting a culture of access to information at the local level. Thus, within our engagement in the implementation of the Social Accountability Framework (more details here), we keep pushing for commune, district and provincial administrations, as well as public service providers to release their policy plans, budgets or performance data to the public. We are also advocating for functional and accessible ombudsperson offices to be established locally, as a mechanism to effectively enforce transparency. It is a long and cumbersome way, but we are convinced that it actually is the only way forward.